In 2015, 屠呦呦 (Tu Youyou) ended her Nobel lecture with a recitation of a poem by 王之渙 (Wang Zhihuan), a Tang dynasty poet:

登鹳雀楼

白日依山尽

黄河入海流

欲穷千里目

更上一层楼

Climbing the Stork Tower

The sun along the mountain bows;

The Yellow River seawards flows.

You will enjoy a grander sight,

if you climb to a greater height.

白日依山尽

黄河入海流

欲穷千里目

更上一层楼

Climbing the Stork Tower

The sun along the mountain bows;

The Yellow River seawards flows.

You will enjoy a grander sight,

if you climb to a greater height.

The poem emblematizes Tu Youyou's road to discovering artemisinin - at once deeply rooted in the spirit of Chinese tradition while also driven by the pursuit of knowledge and innovation. I find her scientific journey to be almost mythical, and count her as one of my greatest inspirations (as an aspiring researcher myself).

Born in 1930 in Ningbo, Zhejiang, Tu Youyou set out to study medicine after recovering from a 2 year bout of Tuberculosis that kept her out of school. She studied both both Western and traditional Chinese medicine at the Department of Pharmacy at the Medical School of Peking University. About her time studying Chinese medicine, she cited the following Shakespeare quote:

凡是过去,皆为序章

What's past is prologue

What's past is prologue

Indeed, it's hard to have predicted exactly how the past would have led to the work she did, but it all came together in a beautiful way. When the Cultural Revolution came, academic research stalled, and her husband was sent to "re-education" camp, causing further difficulties in how to take care of her two young children. Soon, though, Tu Youyou became appointed to head the traditional Chinese medicine arm of Project 523, a secret military project to find a cure for malaria.

It was the late 1960s in the jungles of Vietnam, and malaria had been ravaging the troops of the Viet Cong. Ho Chih Minh had requested help from Mao Zedong - malaria was becoming resistant to chloroquine, and a new cure was needed.

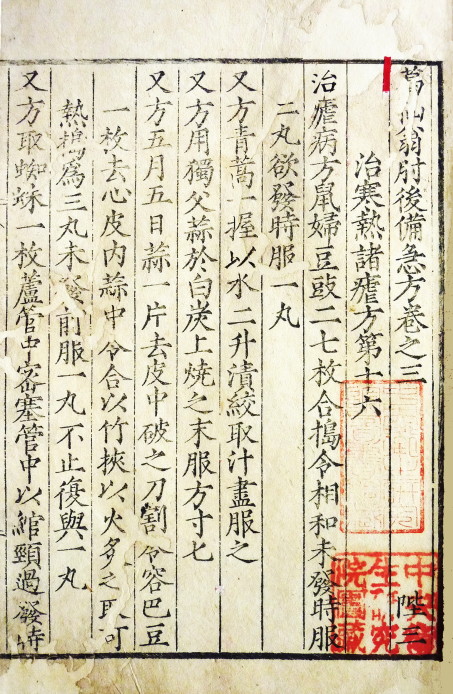

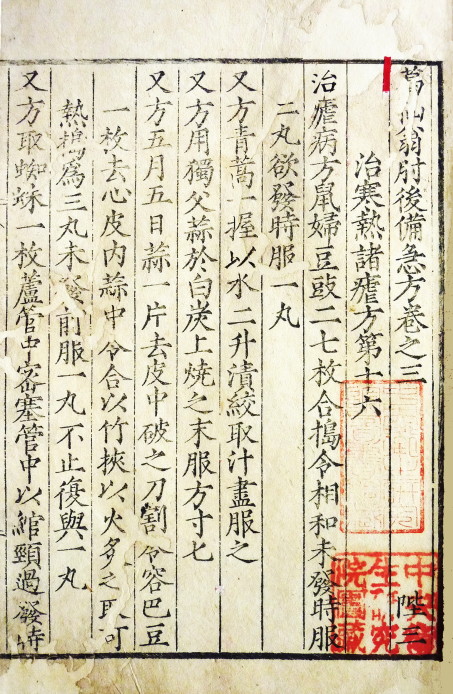

The hunt for a cure had been afoot for a while. Worldwide, scientists had tested over 240,000 different compounds, but none had been successful. Taking a different path from Western medicine, Tu Youyou and her team turned towards traditional Chinese medicine to find a cure. She and her team consulted traditional medicine experts and scoured ancient texts for clues, collecting a list of over 2000 herbal and animal remedies that had been used to treat malaria. A promising lead came from a 4th century text called The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies, by Ge Hong.

青蒿一握 以水二升渍 绞取汁 尽服之

Take a handful of qinghao, place in two liters of water, squeeze it dry, then consume it all

Take a handful of qinghao, place in two liters of water, squeeze it dry, then consume it all

The usual method of extracting the active compounds from herbal remedies was to boil them in water, but interestingly this description called to just soak it. Tu Youyou suspected that heat would destroy the active compounds, and so she distilled it using ethyl ether (a boiling point of 34.6°C).

In 1971, sample 191 of the qinghao extract was tested on mice. The extract was administered orally at a dose of 1.0 g/kg for three consecutive days. achieved 100% effectiveness in curing malaria. Soon after came trials with monkeys, which also achieved a 100% cure rate. Then, to expedite the lengthy drug approval process, Tu Youyou volunteered to be the first human subject. Success.

In English the qinghao plant is called "Sweet Wormword", or in scientific terms Artemisia annua". The active compound was named "artemisinin". In 1977 Tu Youyou published her findings on artemisinin anonymously. Then in 1986 artemisinin received a China Ministry of Health New Drug Certificate.

青蒿素高效缩小低度

Artemisinin is effective, fast, and has low toxicity

Artemisinin is effective, fast, and has low toxicity

Artemisinin and its derivatives are now the most effective treatment for malaria, and have saved millions of lives. In 2017, malaria would be completely eradicated in China.

But now that this cure was found from the two thousand year old annals of Chinese medicine, Western medicine was used to refine the drug. One of the first uses of X-ray crystallography in all of China was to determine the structure of artemisinin - in particular, to make sure it was distinct from chloroquine. Further analysis determined that artemisinin was previously unknown sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxyl group.

Tu Youyou determined that this peroxyl group was the key to artemisinin's antimalarial properties. It is suspected that heme, a byproduct of hemoglobin breakdown, reacts with artemisinin to activate it, allowing it to bond indiscrimantely to essential proteins and completely destroy all functions of the malaria parasite. As such, the destructive properties of artemisinin are only activated inside the hemoglobin-digesting parasite, and not in the human host. This indiscriminate attacking of proteins also makes it difficult for the parasite to develop resistance to artemisinin.

Later, Tu Youyou modified artemisinin into the derviative dihydroartemisinin, which was then further modified into arteether, artesunate, and artemether, all of which contain the peroxyl group and are effective in treating malaria.

I find that the thematic elements of Tu Youyou's work, combining traditional folk methods with modern scientific insight in service of the greater good.

The mythos of her journey is also a source of awe and wonder to me. Interestingly, even her name given at birth had an element of foreshadowing to it. Her dad named her "Youyou" after a line in the 诗经, or Chinese Book of Odes, which goes:

呦呦鹿鸣, 食野之蒿

Deer bleat "youyou" while they are eating the wild hao

Deer bleat "youyou" while they are eating the wild hao

Mysterious.

Well, that's enough romanticizing. There's one more note about her story that she publicized - about how much she had to sacrifice in order to pursue the research that she did. As her husband was sent away, she had to rely on her parents and school to raise her children for her. Tu Youyou writes:

"My younger daughter couldn’t recognize me when I visited my parents three years later, and my elder daughter hid behind her teacher when I picked her up upon returning to Beijing after a clinical investigation."

I believe she currently continues to work as chief scientist of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, and live with her family in Beijing. For decades after her discoveries she continued to work in obscurity, only receiving the bulk of her recognition in the 2010s and the Nobel Prize in 2015. Maybe part of it is the culture of collectivism vs individualism in China, but I think it's also a testament to her humility and dedication to her work.

It's hard to really know the person behind the legend and tease apart all the elements of someone's story. Even so, I think Tu Youyou's story is one that I will continue to look up to throughout my own journey in research. And maybe I'll write up more things like this. This was a jotting down of some thoughts after I found one of my old powerpoints from class about her (attached).